Complete article

Excavations in Judean foothills uncover small jug from 1,100 BCE that could be inscribed with ‘Jerubbaal’; first evidence of a name from Book of Judges on a contemporary artifact

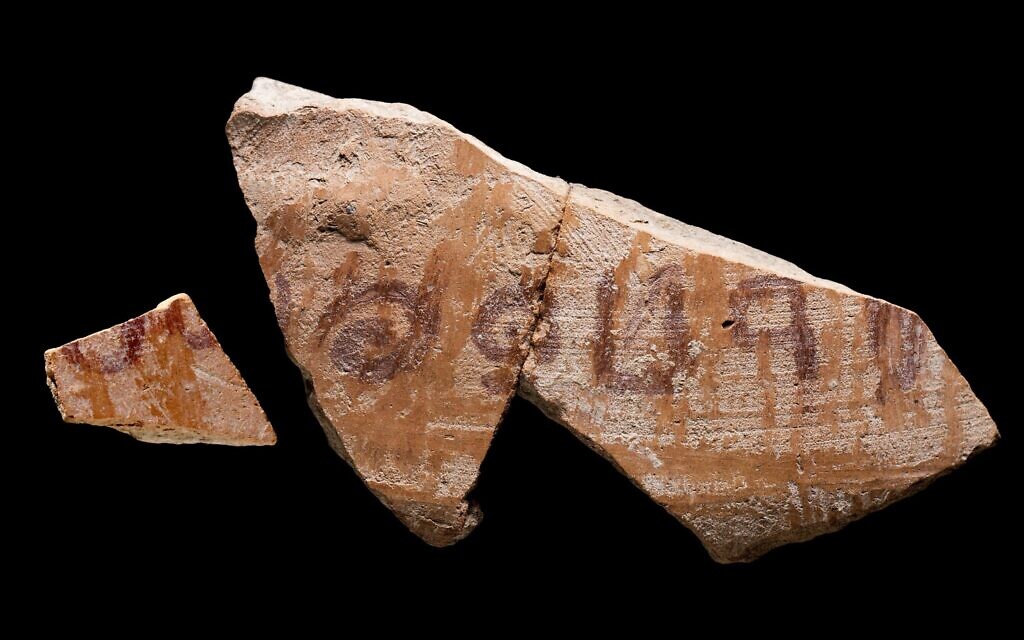

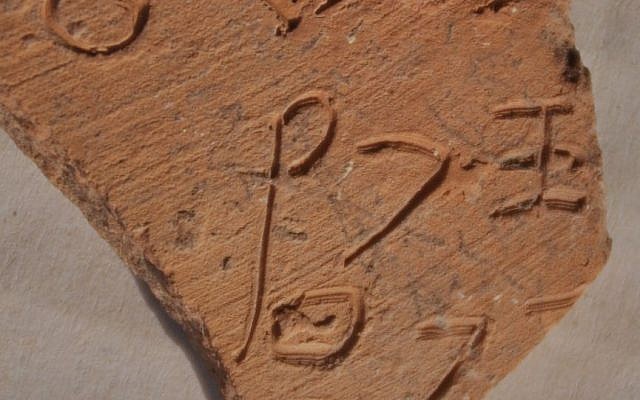

The 'Jerubbaal' inscription, written in ink on a pottery vessel, discovered at Khirbet el Rai. (Dafna Gazit, Israel Antiquities Authority)

The 'Jerubbaal' inscription, written in ink on a pottery vessel, discovered at Khirbet el Rai. (Dafna Gazit, Israel Antiquities Authority) Aerial view of Khirbet el Rai, near Lachish in central Israel. (Emil Aladjem, Israel Antiquities Authority)

Aerial view of Khirbet el Rai, near Lachish in central Israel. (Emil Aladjem, Israel Antiquities Authority) The 'Jerubbaal' inscription, written in ink on a pottery vessel, discovered at Khirbet el Rai. (Dafna Gazit, Israel Antiquities Authority)

The 'Jerubbaal' inscription, written in ink on a pottery vessel, discovered at Khirbet el Rai. (Dafna Gazit, Israel Antiquities Authority) Excavation of the silo where the Jerubbaal inscription was found. (Yossi Garfinkel, Hebrew University of Jerusalem)

Excavation of the silo where the Jerubbaal inscription was found. (Yossi Garfinkel, Hebrew University of Jerusalem) Excavating a jar from the time of the biblical Judges at Khirbet el Rai. (Sa‘ar Ganor, Israel Antiquities Authority)

Excavating a jar from the time of the biblical Judges at Khirbet el Rai. (Sa‘ar Ganor, Israel Antiquities Authority) Sa‘ar Ganor, Israel Antiquities Authority, at Khirbet el Rai. (Emil Aladjem, Israel Antiquities Authority)

Sa‘ar Ganor, Israel Antiquities Authority, at Khirbet el Rai. (Emil Aladjem, Israel Antiquities Authority) Aerial view of Khirbet el Rai, near Lachish in central Israel. (Emil Aladjem, Israel Antiquities Authority)

Aerial view of Khirbet el Rai, near Lachish in central Israel. (Emil Aladjem, Israel Antiquities Authority)

Inked 3,100 years ago during the era of the biblical judges, an extremely rare five-letter inscription discovered in the lush Judean foothills could be a missing link in the development of Early Alphabetic (also known as Canaanite) writing used during the 12th-10th centuries BCE.

If correct, this would be the first hard evidence of a name from the biblical stories of the judges that is on an artifact contemporary to the period.

The inscription was published Monday as part of the second issue of the Jerusalem Journal of Archaeology (JJAR) — a new open-access online journal — edited by Bar-Ilan Prof. Avraham Faust, Hebrew University Prof. Yossef Garfinkel, and Hebrew University researcher Dr. Madeleine Mumcuoglu.

The painted pottery is dated by the archaeologists to 1,100 BCE, which would make it prior to the formation of the biblical monarchy. The inscription was written in Early Alphabetic/Canaanite script, evidence of which has been found throughout Egypt and the Levant. First finds including paleo-Hebrew script come much later, dating to the 9th century BCE.

According to a cross-institutional team of archaeologists and epigraphers, the partial inscription, painted on three pottery sherds from an incomplete small vessel, is most logically read as “Jerubbaal” or “Yeruba’al,” which was the nickname of the biblical judge Gideon, son of Joash, who was active in the northern parts of the Land of Israel during this era.

“The reading Yeruba’al is the most logical and reasonable reading, and I consider it quite definitive,” epigrapher Prof. Christopher Rollston from George Washington University, who deciphered the text, told The Times of Israel. “I would hasten to add that this script is well known and nicely attested, so we can read it with precision.”

The inscription joins a mere handful of others that were found in the Land of Israel from a similar time period. Arguably, one of the earliest was discovered in the 1970s in Izbet-Sarta, followed by several other 12th-10th century BCE inscription discoveries in the past 15 years, including in Tell eṣ-Ṣafi, Khirbet Qeiyafa, Jerusalem, Lachish.

According to the archaeologists, the newly discovered inscription serves as a textual bridge for the transition from the Canaanite to the Israelite and Judahite cultures.

“For decades, there were practically no inscriptions of this era and region. To the point that we were not even sure what the alphabet looked like at that time. There was a gap. Some even argued that the alphabet was unknown in the region, that there were no scribes, and that the Bible must therefore have been written much later,” polymath independent epigrapher and historian Michael Langlois told The Times of Israel.

“These inscriptions are still rare, but they are slowly filling the gap; they not only document the evolution of the alphabet, they show that there was in fact continuity in culture, language and traditions. The implications for our understanding of biblical history are vast — and exciting!” said Langlois, who was not involved in this current excavation.

At Khirbet el Rai

The inscription was discovered at the Khirbet el Rai site, located between Kiryat Gat and Lachish, about 70 kilometers (43 miles) southwest of Jerusalem. Since 2015, the site has been excavated by the Hebrew University of Jerusalem’s Prof. Yossef Garfinkel, the Israel Antiquities Authority’s Sa’ar Ganor, and Dr. Kyle Keimer and Dr. Gil Davies of Macquarie University in Sydney.

According to Ganor, the site includes impressively large structures from the 12th, 11th and 10th centuries BCE. “If you’d like a biblical parallel, we’re talking about the days of the judges and King David,” he said in an IAA Hebrew-language film.

Excavating among the area’s vineyards, the team has found evidence of a Philistine-era settlement from the 12-11th centuries BCE under layers of a rural settlement dating to the early 10th century BCE, largely considered the Davidic era. Among the findings were massive stone structures and typical Philistine cultural artifacts, including pottery in foundation deposits — good luck offerings laid beneath a building’s flooring.

Archaeologist Garfinkel told The Times of Israel that the dating of the pottery piece was accomplished through a confluence of methods including radiocarbon-14 dating from the stratum just above this find, which gave a result of 1050 BCE, the typography of the pottery sherds found with the inscription, and petrographic analysis of the inscribed pottery that was completed by Ariel University’s Prof. David Ben-Shlomo, who concluded that the small liter-sized jug was locally made.

GHe emphasized that while it is thrilling and important to find hard evidence of a name included in the Bible, what is even more important is filling what he calls a “missing link” in the Canaanite script. He said that there have been examples discovered from the 14th, 13th, and the first half of the 12th century — but then there was a mysterious period of 150 years of no discovered inscriptions that connected between Canaanite inscriptions and Judean script.

This discovery, he said, would have been “very important even if was just letters without meaning. But in this case, we also have a name from the biblical period.”

The inscription is partial, but the word “ba’al” can clearly be read in it, which was a somewhat common name in the Bible from sections that could have taken place during the 11th-10th centuries. This hard evidence dating from the same era, said Garfinkel, helps shore up what he repeatedly called an “onomastic horizon” — i.e., the proof of the common use of “ba’al” in personal names.

The use of “ba’al” can be tied to the strong pagan warrior god, or to “lord,” said Garfinkel. He hypothesized that as the peoples came to worship the Israelite god more in following centuries, the onomastic horizon again shifted to include “yahu” — the Israelite god — instead of “ba’al,” with names such as Yirmiyahu (Jeremiah) and Eliyahu (Elijah).

“For the peoples who believed in strong warrior god, sometime over time the Canaanite ‘ba’al’ became the Israelite ‘yahu,'” said Garfinkel.

Scribes who wrote the developing Early Alphabetic script painted on the newly discovered inscription did not use punctuation and were not particular about the directions in which letters lay. It is quite possible that letters came before and after the four clear letters found on the pottery — spelling resh, bet, ayin, and lamed — and the partial letter that has been identified by Rollston as yud.

According to Hebrew University epigrapher Dr. Haggai Misgav, “the variability of this script is well known.” He believes that according to the letters’ shapes, the dating of 1,100 BCE is quite possible; however, because the inscription is partial, he is not convinced that “Jerubbaal” is the only reading of the letters. “I can think about ‘Azruba’al — the first seen letter could be zayin, and maybe there is an ‘ayin before it,” he spitballed to The Times of Israel.

Likewise, epigrapher Langlois said that there were still plenty of options on the table before definitely arriving at “Jerubbaal.”

“The inscription is fragmentary, which calls for caution. But this kind of inscription often bears personal names, which often feature the name of a deity… Supposing that what we have is a name ending in -baal, and that the previous letter is a resh, there are a number of candidates already attested: Zekharbaal, Maribaal, Jerubbaal etc. And of course it could also be a name not yet attested, which is not uncommon, as our knowledge of that period of history is quite limited. The key is thus the identification of yud at the beginning of the line,” said Langlois.

Regarding the partial letter, Rollston said, “The shape of that letter is most consistent with a yud. (It should be remembered that with this very early script, the stance of a letter, that is, the way that it is rotated, can vary a great deal) Thus, it is the shape of that letter which is the crucial part… and the shape is most consistent with a yud.”

Regarding playing Boggle with other potential letters to arrive at different readings, Rollston said that there is no visible letter prior to the yud — “thus, to posit that an ayin is present is pure speculation…and I don’t consider speculation to be a good method.”

Or, as Garfinkel put it, “We have resh, beit, ayin, and lamed, and nearby there is another letter, which is a bit broken… The most stable ground is to reconstruct the minimal possible name, which is Jerubbaal.”

No comments:

Post a Comment