University of Arizona researchers have cracked one of the puzzles surrounding what has been called "the world's most mysterious manuscript" -- the Voynich manuscript, a book filled with drawings and writings nobody has been able to make sense of to this day.

Using radiocarbon dating, a team led by Greg Hodgins in the UA's department of physics has found the manuscript's parchment pages date back to the early 15th century, making the book a century older than scholars had previously thought.

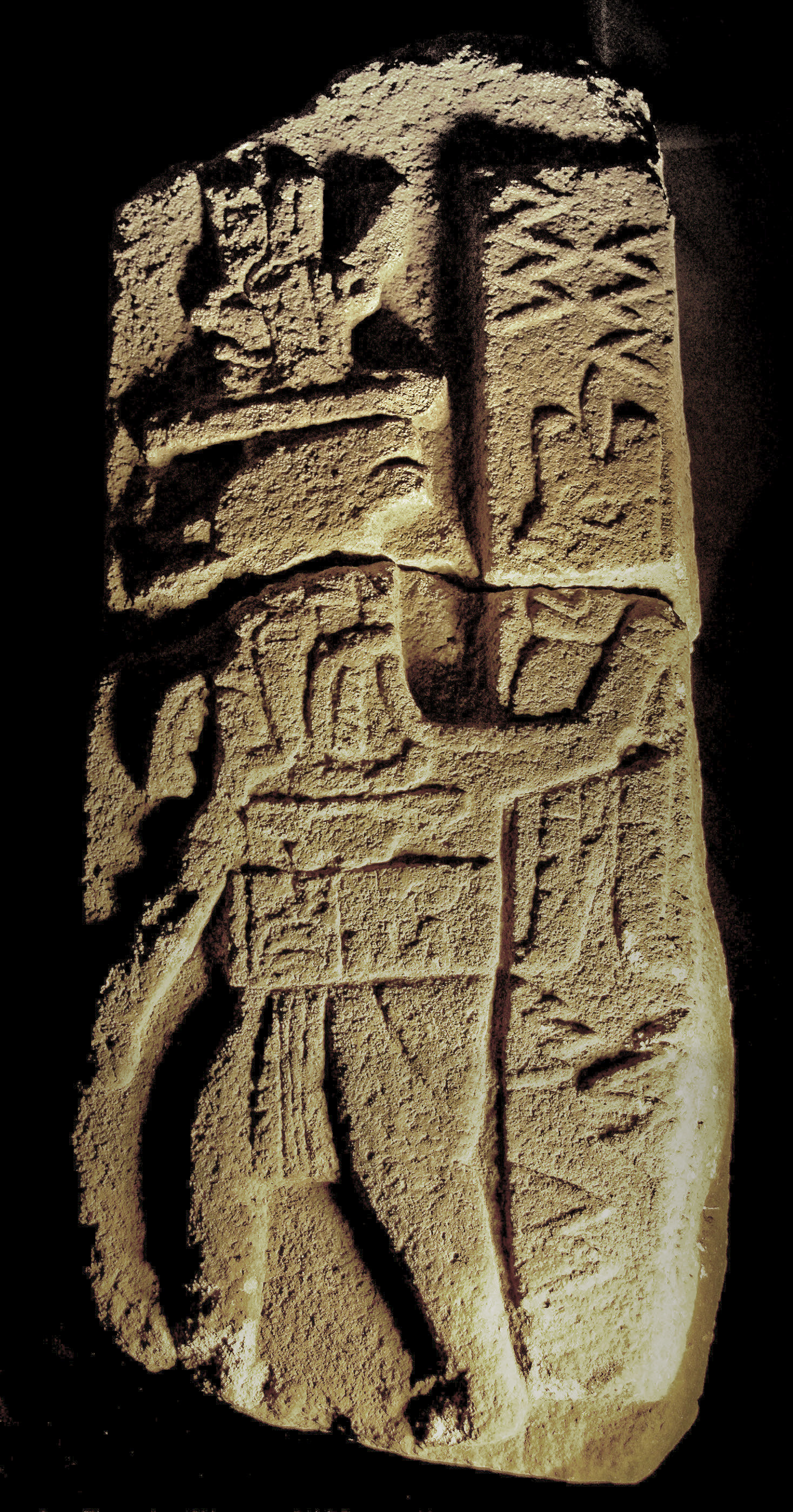

This tome makes the "DaVinci Code" look downright lackluster: Rows of text scrawled on visibly aged parchment, flowing around intricately drawn illustrations depicting plants, astronomical charts and human figures bathing in -- perhaps -- the fountain of youth. At first glance, the "Voynich manuscript" appears to be not unlike any other antique work of writing and drawing.

An alien language

But a second, closer look reveals that nothing here is what it seems. Alien characters, some resembling Latin letters, others unlike anything used in any known language, are arranged into what appear to be words and sentences, except they don't resemble anything written -- or read -- by human beings.

Hodgins, an assistant research scientist and assistant professor in the UA's department of physics with a joint appointment at the UA's School of Anthropology, is fascinated with the manuscript.

"Is it a code, a cipher of some kind? People are doing statistical analysis of letter use and word use -- the tools that have been used for code breaking. But they still haven't figured it out."

A chemist and archaeological scientist by training, Hodgins works for the NSF Arizona Accelerator Mass Spectrometry, or AMS, Laboratory, which is shared between physics and geosciences. His team was able to nail down the time when the Voynich manuscript was made.

Currently owned by the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library of Yale University, the manuscript was discovered in the Villa Mondragone near Rome in 1912 by antique book dealer Wilfrid Voynich while sifting through a chest of books offered for sale by the Society of Jesus. Voynich dedicated the remainder of his life to unveiling the mystery of the book's origin and deciphering its meanings. He died 18 years later, without having wrestled any its secrets from the book.

Fast-forward to 2009: In the basement underneath the UA's Physics and Atmospheric Sciences building, Hodgins and a crew of scientists, engineers and technicians stare at a computer monitor displaying graphs and lines. The humming sound of machinery fills the room and provides a backdrop drone for the rhythmic hissing of vacuum pumps.

Stainless steel pipes, alternating with heavy-bodied vacuum chambers, run along the walls.

This is the heart of the NSF-Arizona AMS Laboratory: an accelerator mass spectrometer capable of sniffing out traces of carbon-14 atoms that are present in samples, giving scientists clues about the age of those samples.

Radiocarbon dating: looking back in time

Carbon-14 is a rare form of carbon, a so-called radioisotope, that occurs naturally in Earth's environment. In the natural environment, there is only one carbon-14 atom per trillion non-radioactive or "stable" carbon isotopes, mostly carbon-12, but with small amounts of carbon-13. Carbon-14 is found in the atmosphere within carbon dioxide gas.

Plants produce their tissues by taking up carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, and so accumulate carbon-14 during life. Animals in turn accumulate carbon-14 in their tissues by eating plants, or eating other organisms that consume plants.

When a plant or animal dies, the level of carbon-14 in it remains drops at a predictable rate, and so can be used to calculate the amount of time that has passed since death.

What is true of plants and animals is also true of products made from them. Because the parchment pages of the Voynich Manuscript were made from animal skin, they can be radiocarbon-dated.

Pointing to the front end of the mass spectrometer, Hodgins explains the principle behind it. A tiny sample of carbon extracted from the manuscript is introduced into the "ion source" of the mass spectrometer.

"This causes the atoms in the sample to be ionized," he explained, "meaning they now have an electric charge and can be propelled by electric and magnetic fields."

Ejected from the ion source, the carbon ions are formed into a beam that races through the instrument at a fraction of the speed of light. Focusing the beam with magnetic lenses and filters, the mass spectrometer then splits it up into several beams, each containing only one isotope species of a certain mass.

"Carbon-14 is heavier than the other carbon isotopes," Hodgins said. "This way, we can single out this isotope and determine how much of it is present in the sample. From that, we calculate its age."

Dissecting a century-old book

To obtain the sample from the manuscript, Hodgins traveled to Yale University, where conservators had previously identified pages that had not been rebound or repaired and were the best to sample.

"I sat down with the Voynich manuscript on a desk in front of me, and delicately dissected a piece of parchment from the edge of a page with a scalpel," Hodgins says.

He cut four samples from four pages, each measuring about 1 by 6 millimeters (ca. 1/16 by 1 inch) and brought them back to the laboratory in Tucson, where they were thoroughly cleaned.

"Because we were sampling from the page margins, we expected there are a lot of finger oils adsorbed over time," Hodgins explains. "Plus, if the book was re-bound at any point, the sampling spots on these pages may actually not have been on the edge but on the spine, meaning they may have had adhesives on them."

"The modern methods we use to date the material are so sensitive that traces of modern contamination would be enough to throw things off."

Next, the sample was combusted, stripping the material of any unwanted compounds and leaving behind only its carbon content as a small dusting of graphite at the bottom of the vial.

"In radiocarbon dating, there is this whole system of many people working at it," he said. "It takes many skills to produce a date. From start to finish, there is archaeological expertise; there is biochemical and chemical expertise; we need physicists, engineers and statisticians. It's one of the joys of working in this place that we all work together toward this common goal."

The UA's team was able to push back the presumed age of the Voynich manuscript by 100 years, a discovery that killed some of the previously held hypotheses about its origins and history.

Elsewhere, experts analyzed the inks and paints that makes up the manuscript's strange writings and images.

"It would be great if we could directly radiocarbon date the inks, but it is actually really difficult to do. First, they are on a surface only in trace amounts" Hodgins said. "The carbon content is usually extremely low. Moreover, sampling ink free of carbon from the parchment on which it sits is currently beyond our abilities. Finally, some inks are not carbon based, but are derived from ground minerals. They're inorganic, so they don't contain any carbon."

"It was found that the colors are consistent with the Renaissance palette -- the colors that were available at the time. But it doesn't really tell us one way or the other, there is nothing suspicious there."

While Hodgins is quick to point out that anything beyond the dating aspect is outside his expertise, he admits he is just as fascinated with the book as everybody else who has tried to unveil its history and meaning.

"The text shows strange characteristics like repetitive word use or the exchange of one letter in a sequence," he says. "Oddities like that make it really hard to understand the meaning."

"There are types of ciphers that embed meaning within gibberish. So it is possible that most of it does mean nothing. There is an old cipher method where you have a sheet of paper with strategically placed holes in it. And when those holes are laid on top of the writing, you read the letters in those holes."

"Who knows what's being written about in this manuscript, but it appears to be dealing with a range of topics that might relate to alchemy. Secrecy is sometimes associated with alchemy, and so it would be consistent with that tradition if the knowledge contained in the book was encoded. What we have are the drawings. Just look at those drawings: Are they botanical? Are they marine organisms? Are they astrological? Nobody knows."

"I find this manuscript is absolutely fascinating as a window into a very interesting mind. Piecing these things together was fantastic. It's a great puzzle that no one has cracked, and who doesn't love a puzzle?