Ω

Western Europe has long been held to be the "cradle" of Neandertal evolution since many of the earliest discoveries were from sites in this region. But when Neandertals started disappearing around 30,000 years ago, anthropologists figured that climactic factors or competition from modern humans were the likely causes.

But new research suggests that Western European Neandertals were on the verge of extinction long before modern humans showed up. This new perspective comes from a study of ancient DNA carried out by an international research team. Rolf Quam, a Binghamton University anthropologist, was a co-author of the study led by Anders Götherström at Uppsala University and Love Dalén at the Swedish Museum of Natural History, and published in the journal Molecular Biology and Evolution.

"The Neandertals are our closest fossil relatives and abundant evidence of their lifeways and skeletal remains have been found at many sites across Europe and western Asia," said Quam, assistant professor of anthropology. "Until modern humans arrived on the scene, it was widely thought that Europe had been populated by a relatively stable Neandertal population for hundreds of thousands of years. Our research suggests otherwise and in light of these new results, this long-held theory now faces scrutiny."

Focusing on mitochondrial DNA sequences from 13 Neandertal individuals, including a new sequence from the site of Valdegoba cave in northern Spain, the research team found some surprising results. When they first started looking at the DNA, a clear pattern emerged. Neandertal individuals from western Europe that were older than 50,000 years and individuals from sites in western Asia and the Middle East showed a high degree of genetic variation, on par with what might be expected from a species that had been abundant in an area for a long period of time. In fact, the amount of genetic variation was similar to what characterizes modern humans as a species. In contrast, Neandertal individuals that come from Western Europe and are younger than 50,000 years show an extremely reduced amount of genetic variation, less even than the present-day population of remote Iceland.

These results suggest that western European Neandertals went through a demographic crisis, a population bottleneck that severely reduced their numbers, leaving Western Europe largely empty of humans for a period of time. The demographic crisis seems to coincide with a period of extreme cold in Western Europe. Subsequently, this region was repopulated by a small group of individuals from a surrounding area. The geographic origin of this source population is currently not clear, but it may be possible to pinpoint it further with more Neandertal sequences in the future.

"The fact that Neandertals in western Europe were nearly extinct, but then recovered long before they came into contact with modern humans came as a complete surprise to us," said Dalén, associate professor at the Swedish Museum of Natural History in Stockholm. "This indicates that the Neandertals may have been more sensitive to the dramatic climate changes that took place in the last Ice Age than was previously thought."

Quam concurs and suggests that this discovery calls for a major rethink of the idea of cold adaptation in Neandertals.

"At the very least, this tells us that without the aid of material culture or technology, there is a limit to our biological adaptation," said Quam. "It may very well have been the case that the European Neandertal populations were already demographically stressed when modern humans showed up on the scene."

The results presented in the study are based entirely on severely degraded ancient DNA, and the analyses have therefore required both advanced laboratory and computational methods. The research team has involved experts from a number of countries, including statisticians, experts on modern DNA sequencing and paleoanthropologists from Sweden, Denmark, Spain and the United States.

"This is just the latest example of how studies of ancient DNA are providing new insights into an important and previously unknown part of Neandertal history, "said Quam. "Ancient DNA is complementary to anthropological studies focusing on the bony anatomy of the skeleton, and these kinds of results are only possible with ancient DNA studies. It's exciting to think about what will turn up next."

Monday, March 26, 2012

Saturday, March 24, 2012

The Jury Is Still Out On Question Of Forgeries

Ω

Complete article

Despite the recent verdict of Judge Aharon Farkash of the Jerusalem District Court acquitting accused Israeli forgers Oded Golan and Robert Deutsch, the jury is still very much out on the actual authenticity of the subject antiquities they were accused of forging. After a seven-year trial with 120 sessions where the judge heard 126 witnesses and dozens of experts, producing 12,000 pages of testimony with a final 475-page verdict, the world seems to be no closer than before to determining the truth about the antiquities in question. Among them, the James Ossuary inscription, the Jehoash Tablet inscription, and the diminutive Ivory Pomegranate inscription, await further research and testing before most or all experts can agree that they are, in fact, what they have been purported to be...

Close-up of the Aramaic inscription: “Ya'akov bar Yosef akhui di Yeshua” (“James, son of Joseph, brother of Jesus”, found on an ancient ossuary (bone box, used to encase the collected bones of the deceased after the initial decay of the body after death), purportedly originally found in the Jerusalem area. The find made headlines as the first artifact found to show physical evidence of the existence of Jesus of Nazareth, his brother James, and father Joseph, as recorded in the Gospels of the New Testament. Paradiso, Wikimedia Commons.

The Ivory Pomegranate, a small decorative object said to have topped a priestly staff. Made of Hippopotamus bone, it bears an inscription, "Belonging to the Temple [literally 'house'] of ---h, holy to the priests" or "Sacred donation for the priests of [or 'in'] the Temple [literally 'house'] of ---. When it was discovered, it was thought to be part of the High Priest sceptre used within the Holy of Holies section of the Jerusalem First Temple (the Temple of Solomon). The bone was once considered a genuine artifact proving the existence of Solomon's Temple, but has since been found to be 300 to 400 years older than the first temple and the inscription has been challenged as a modern forgery due to the Hebraic inscription allegedly being made after it had broken into 1/3 of its original size. Wikimedia Commons

Complete article

Despite the recent verdict of Judge Aharon Farkash of the Jerusalem District Court acquitting accused Israeli forgers Oded Golan and Robert Deutsch, the jury is still very much out on the actual authenticity of the subject antiquities they were accused of forging. After a seven-year trial with 120 sessions where the judge heard 126 witnesses and dozens of experts, producing 12,000 pages of testimony with a final 475-page verdict, the world seems to be no closer than before to determining the truth about the antiquities in question. Among them, the James Ossuary inscription, the Jehoash Tablet inscription, and the diminutive Ivory Pomegranate inscription, await further research and testing before most or all experts can agree that they are, in fact, what they have been purported to be...

Close-up of the Aramaic inscription: “Ya'akov bar Yosef akhui di Yeshua” (“James, son of Joseph, brother of Jesus”, found on an ancient ossuary (bone box, used to encase the collected bones of the deceased after the initial decay of the body after death), purportedly originally found in the Jerusalem area. The find made headlines as the first artifact found to show physical evidence of the existence of Jesus of Nazareth, his brother James, and father Joseph, as recorded in the Gospels of the New Testament. Paradiso, Wikimedia Commons.

The Ivory Pomegranate, a small decorative object said to have topped a priestly staff. Made of Hippopotamus bone, it bears an inscription, "Belonging to the Temple [literally 'house'] of ---h, holy to the priests" or "Sacred donation for the priests of [or 'in'] the Temple [literally 'house'] of ---. When it was discovered, it was thought to be part of the High Priest sceptre used within the Holy of Holies section of the Jerusalem First Temple (the Temple of Solomon). The bone was once considered a genuine artifact proving the existence of Solomon's Temple, but has since been found to be 300 to 400 years older than the first temple and the inscription has been challenged as a modern forgery due to the Hebraic inscription allegedly being made after it had broken into 1/3 of its original size. Wikimedia Commons

Monday, March 19, 2012

Beer and Bling in Iron Age Europe

Ω

If you wanted to get ahead in Iron-Age Central Europe you would use a strategy that still works today – dress to impress and throw parties with free alcohol.

Pre-Roman Celtic people practiced what archaeologist Bettina Arnold calls “competitive feasting,” in which people vying for social and political status tried to outdo one another through power partying.

Artifacts recovered from two 2,600-year-old Celtic burial mounds in southwest Germany, including items for personal adornment and vessels for alcohol, offer a glimpse of how these people lived in a time before written records were kept.

That was the aim of the more than 10-year research project, says Arnold, anthropology professor at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and co-director of a field excavation at the Heuneburg hillfort in German state of Baden-Wurttemberg.

In fact, based on the drinking vessels found in graves near the hillfort settlement and other imported objects, archaeologists have concluded the central European Celts were trading with people from around the Mediterranean.

Braü or mead?

“Beer was the barbarian’s beverage, while wine was more for the elite, especially if you lived near a trade route,” says Kevin Cullen, an archaeology project associate at Discovery World in Milwaukee and a former graduate student of Arnold’s.

Since grapes had not yet been introduced to central Europe, imported grape wine would indicated the most social status. The Celts also made their own honey-based wine, or mead, flavored with herbs and flowers, that would have been more expensive than beer, but less so than grape wine.

They also made a wheat or barley ale without hops that could be mixed with mead or consumed on its own, but that had to be consumed very soon after being made. “Keltenbräu,” is an example of such an ale. It would have been a dark, roasted ale with a smoky flavor.

To the upper-class, the quantity of alcohol consumed was as important as the quality. Arnold excavated at least one fully intact cauldron used for serving alcoholic beverages in one of the graves at Heuneburg. But it’s hard to top the recovery of nine drinking horns – including one that held 10 pints – at a single chieftain’s grave in nearby Hochdorf in the 1970s.

Dapper dudes and biker chicks

In addition to their fondness for alcohol, Celtic populations from this period were said by the Greeks and Romans to favor flashy ornament and brightly striped and checked fabrics, says Arnold. The claim has always been difficult to confirm, however, since cloth and leather are perishable.

The Heuneburg mounds yielded evidence of both, even though no bones remain due to acidic soil. But the team of archaeologists were able to reconstruct elements of dress and ornamentation using new technology.

Rather than attempt to excavate fragile metal remains, such as hairpins, jewelry, weapons and clothing fasteners, Arnold and her colleagues encased blocks of earth containing the objects in plaster, then put the sealed bundles through a computerized tomography, or CT, scanner.

“We found fabulous leather belts in some of the high-status women’s graves, with thousands of tiny bronze staples attached to the leather that would have taken hours to make,” she says. “I call them the Iron-Age Harley-Davidson biker chicks.”

Images show such fine detail, the archaeologists theorize that some of the items were not just for fashion.

“You could tell whether someone was male, female, a child, married, occupied a certain role in society and much more from what they were wearing.”

The pins that secured a veil to a woman’s head, for example, also appear to symbolize marital status and perhaps motherhood. Other adornment was gender-specific – bracelets worn on the left arm were found in men’s graves, but bracelets worn on both arms and neck rings were found only in graves of women.

Surprisingly, it was the metal implements in close contact with linen and wool textiles in the graves that provided a chance for their preservation. Bits of fabric clinging to metal allowed the archaeologists to use microscopic inspection to recreate the colors and patterns used.

“When you can actually reconstruct the costume,” says Arnold, “all of a sudden these people are ‘there’ – in three dimensions. They have faces. They can almost be said to have personalities at that point.”

If you wanted to get ahead in Iron-Age Central Europe you would use a strategy that still works today – dress to impress and throw parties with free alcohol.

Pre-Roman Celtic people practiced what archaeologist Bettina Arnold calls “competitive feasting,” in which people vying for social and political status tried to outdo one another through power partying.

Artifacts recovered from two 2,600-year-old Celtic burial mounds in southwest Germany, including items for personal adornment and vessels for alcohol, offer a glimpse of how these people lived in a time before written records were kept.

That was the aim of the more than 10-year research project, says Arnold, anthropology professor at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and co-director of a field excavation at the Heuneburg hillfort in German state of Baden-Wurttemberg.

In fact, based on the drinking vessels found in graves near the hillfort settlement and other imported objects, archaeologists have concluded the central European Celts were trading with people from around the Mediterranean.

Braü or mead?

“Beer was the barbarian’s beverage, while wine was more for the elite, especially if you lived near a trade route,” says Kevin Cullen, an archaeology project associate at Discovery World in Milwaukee and a former graduate student of Arnold’s.

Since grapes had not yet been introduced to central Europe, imported grape wine would indicated the most social status. The Celts also made their own honey-based wine, or mead, flavored with herbs and flowers, that would have been more expensive than beer, but less so than grape wine.

They also made a wheat or barley ale without hops that could be mixed with mead or consumed on its own, but that had to be consumed very soon after being made. “Keltenbräu,” is an example of such an ale. It would have been a dark, roasted ale with a smoky flavor.

To the upper-class, the quantity of alcohol consumed was as important as the quality. Arnold excavated at least one fully intact cauldron used for serving alcoholic beverages in one of the graves at Heuneburg. But it’s hard to top the recovery of nine drinking horns – including one that held 10 pints – at a single chieftain’s grave in nearby Hochdorf in the 1970s.

Dapper dudes and biker chicks

In addition to their fondness for alcohol, Celtic populations from this period were said by the Greeks and Romans to favor flashy ornament and brightly striped and checked fabrics, says Arnold. The claim has always been difficult to confirm, however, since cloth and leather are perishable.

The Heuneburg mounds yielded evidence of both, even though no bones remain due to acidic soil. But the team of archaeologists were able to reconstruct elements of dress and ornamentation using new technology.

Rather than attempt to excavate fragile metal remains, such as hairpins, jewelry, weapons and clothing fasteners, Arnold and her colleagues encased blocks of earth containing the objects in plaster, then put the sealed bundles through a computerized tomography, or CT, scanner.

“We found fabulous leather belts in some of the high-status women’s graves, with thousands of tiny bronze staples attached to the leather that would have taken hours to make,” she says. “I call them the Iron-Age Harley-Davidson biker chicks.”

Images show such fine detail, the archaeologists theorize that some of the items were not just for fashion.

“You could tell whether someone was male, female, a child, married, occupied a certain role in society and much more from what they were wearing.”

The pins that secured a veil to a woman’s head, for example, also appear to symbolize marital status and perhaps motherhood. Other adornment was gender-specific – bracelets worn on the left arm were found in men’s graves, but bracelets worn on both arms and neck rings were found only in graves of women.

Surprisingly, it was the metal implements in close contact with linen and wool textiles in the graves that provided a chance for their preservation. Bits of fabric clinging to metal allowed the archaeologists to use microscopic inspection to recreate the colors and patterns used.

“When you can actually reconstruct the costume,” says Arnold, “all of a sudden these people are ‘there’ – in three dimensions. They have faces. They can almost be said to have personalities at that point.”

Thursday, March 15, 2012

Court: "James son of Joseph, brother of Jesus" ossuary inscription not proven as forgery

Ω

Mystery continues to surround an ancient burial box that is inscribed with the words, "James son of Joseph, brother of Jesus," after a Jerusalem court found Oded Golan, a private collector of antiquities, not guilty of forging the inscription.

The court said the 2000-year-old box will probably "continue to be investigated in the archaeological and scientific arena, and time will tell," according to a report from Reuters. The court's decision puts an end to a legal battle that began in 2004 when Golan was indicted.

Read more

The affair began following the surprising appearance of two archaeological exhibits of historical, religious and political importance, which were exposed to the public through the media and left the archaeological world in a state of consternation.

The first exhibit that was revealed is a standard ossuary (a ceramic coffin) that was used for gathering bones in the Second Temple period. What was unique about this particular ossuary was the inscription engraved on its front, according to which it belonged to “James son of Joseph, brother of Jesus”. The ossuary was first displayed in an exhibit in a Canadian museum and garnered world-wide acclaim through the media due to it alleged connection to the family of Jesus of Nazareth.

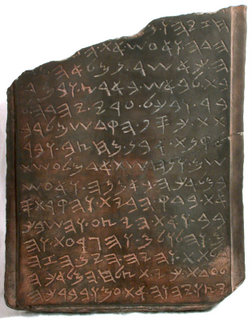

Jehoash inscription

The second item was a building inscription engraved on a stone in ancient Hebrew script, which was attributed to renovations carried out by King Jehoash on the First Temple in the late ninth century BCE. Hence, this is supposedly the only surviving item of the First Temple ever, thus constituting proof of the First Temple’s existence and authentication of the biblical text appearing in the Book of Chronicles.

The appearance of the two items in late 2002 and early 2003 fired the imaginations of millions of Christians around the world, who received tangible proof of Jesus’ family, and of thousands of Jews who ostensibly now had physical evidence from the First Temple and archeological verification of the biblical stories.

The Israel Antiquities Authority, in its capacity as the governmental agency responsible to treat and manage all matters regarding antiquities in the State of Israel, convened two committees of experts to examine the two exhibits. The committee members were selected from amongst the foremost experts in the fields of archaeology, epigraphy and ancillary sciences from the Israel Antiquities Authority and all of the leading universities in Israel. Several months later the experts published their opinion, which stated that both items are modern forgeries: new and modern lettering had been added to the original ossuary; while the Jehoash inscription is an utter forgery.

Other experts obviously disagreed.

Mystery continues to surround an ancient burial box that is inscribed with the words, "James son of Joseph, brother of Jesus," after a Jerusalem court found Oded Golan, a private collector of antiquities, not guilty of forging the inscription.

The court said the 2000-year-old box will probably "continue to be investigated in the archaeological and scientific arena, and time will tell," according to a report from Reuters. The court's decision puts an end to a legal battle that began in 2004 when Golan was indicted.

Read more

The affair began following the surprising appearance of two archaeological exhibits of historical, religious and political importance, which were exposed to the public through the media and left the archaeological world in a state of consternation.

The first exhibit that was revealed is a standard ossuary (a ceramic coffin) that was used for gathering bones in the Second Temple period. What was unique about this particular ossuary was the inscription engraved on its front, according to which it belonged to “James son of Joseph, brother of Jesus”. The ossuary was first displayed in an exhibit in a Canadian museum and garnered world-wide acclaim through the media due to it alleged connection to the family of Jesus of Nazareth.

Jehoash inscription

The second item was a building inscription engraved on a stone in ancient Hebrew script, which was attributed to renovations carried out by King Jehoash on the First Temple in the late ninth century BCE. Hence, this is supposedly the only surviving item of the First Temple ever, thus constituting proof of the First Temple’s existence and authentication of the biblical text appearing in the Book of Chronicles.

The appearance of the two items in late 2002 and early 2003 fired the imaginations of millions of Christians around the world, who received tangible proof of Jesus’ family, and of thousands of Jews who ostensibly now had physical evidence from the First Temple and archeological verification of the biblical stories.

The Israel Antiquities Authority, in its capacity as the governmental agency responsible to treat and manage all matters regarding antiquities in the State of Israel, convened two committees of experts to examine the two exhibits. The committee members were selected from amongst the foremost experts in the fields of archaeology, epigraphy and ancillary sciences from the Israel Antiquities Authority and all of the leading universities in Israel. Several months later the experts published their opinion, which stated that both items are modern forgeries: new and modern lettering had been added to the original ossuary; while the Jehoash inscription is an utter forgery.

Other experts obviously disagreed.

Wednesday, March 7, 2012

Who were the first Americans?

Ω

Complete article

Archaeologists have long held that North America remained unpopulated until about 15,000 years ago, when Siberian people walked or boated into Alaska and then moved down the West Coast.

But a mastodon relic found near the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay turned out to be 22,000 years old, suggesting that the blade found with it was just as ancient.

Whoever fashioned that blade was not supposed to be here.

Its makers probably paddled from Europe and arrived in America thousands of years ahead of the western migration, making them the first Americans, argues Smithsonian Institution anthropologist Dennis Stanford...

At the height of the last ice age, Stanford says, mysterious Stone Age European people known as the Solutreans paddled along an ice cap jutting into the North Atlantic. They lived like Inuits, harvesting seals and seabirds.

The Solutreans eventually spread across North America, Stanford says, hauling their distinctive blades with them and giving birth to the later Clovis culture, which emerged some 13,000 years ago...

At the core of Stanford’s case are stone tools recovered from five mid-Atlantic sites. Two sites lie on Chesapeake Bay islands, suggesting that the Solutreans settled Delmarva early on. Smithsonian research associate Darrin Lowery found blades, anvils and other tools found stuck in soil at least 20,000 years old.

Further, the Eastern Shore blades strongly resemble those found at dozens of Solutrean sites from the Stone Age in Spain and France, Stanford says. “We can match each one of 18 styles up to the sites in Europe...

Ω

Complete article

Archaeologists have long held that North America remained unpopulated until about 15,000 years ago, when Siberian people walked or boated into Alaska and then moved down the West Coast.

But a mastodon relic found near the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay turned out to be 22,000 years old, suggesting that the blade found with it was just as ancient.

Whoever fashioned that blade was not supposed to be here.

Its makers probably paddled from Europe and arrived in America thousands of years ahead of the western migration, making them the first Americans, argues Smithsonian Institution anthropologist Dennis Stanford...

At the height of the last ice age, Stanford says, mysterious Stone Age European people known as the Solutreans paddled along an ice cap jutting into the North Atlantic. They lived like Inuits, harvesting seals and seabirds.

The Solutreans eventually spread across North America, Stanford says, hauling their distinctive blades with them and giving birth to the later Clovis culture, which emerged some 13,000 years ago...

At the core of Stanford’s case are stone tools recovered from five mid-Atlantic sites. Two sites lie on Chesapeake Bay islands, suggesting that the Solutreans settled Delmarva early on. Smithsonian research associate Darrin Lowery found blades, anvils and other tools found stuck in soil at least 20,000 years old.

Further, the Eastern Shore blades strongly resemble those found at dozens of Solutrean sites from the Stone Age in Spain and France, Stanford says. “We can match each one of 18 styles up to the sites in Europe...

Ω

Basque Roots Revealed Through DNA Analysis

Ω

The Genographic Project has announced the most comprehensive analysis to date of Basque genetic patterns, showing that Basque genetic uniqueness predates the arrival of agriculture in the Iberian Peninsula some 7,000 years ago. Through detailed DNA analysis of samples from the French and Spanish Basque regions, the Genographic team found that Basques share unique genetic patterns that distinguish them from the surrounding non-Basque populations.

Published in the American Journal of Human Genetics, the study was led by Lluis Quintana-Murci, principal investigator of Genographic's Western European regional center. "Our study mirrors European history and could certainly extend to other European peoples. We found that Basques share common genetic features with other European populations, but at the same time present some autochthonous (local) lineages that make them unique," said Quintana-Murci. "This is reflected in their language, Euskara, a non-Indo-European language, which altogether contributes to the cultural richness of this European population."

The genetic finding parallels previous studies of the Basque language, which has been found to be a linguistic isolate, unrelated to any other language in the world. It is the ancestral language of the Basque people who inhabit a region spanning northeastern Spain and southwestern France and has long been thought to trace back to the languages spoken in Europe prior to the arrival of the Indo-European languages more than 4,000 years ago. (English, Spanish, French and most other European languages are Indo-European.)

Genographic Project researchers studied mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), which has been widely applied to the study of human history and is perhaps best known as the tool used to reveal 'Mitchondrial Eve,' the female common ancestor of all modern humans who lived in Africa approximately 200,000 years ago. It has also been used to study regional variation both within and outside Africa, providing detailed insights into more recent migration patterns.

The Genographic Project, launched in 2005, enters its eighth year this spring. Nearly 75,000 participants from over 1,000 indigenous populations around the world have joined the initiative, along with more than 440,000 members of the general public who have purchased a testing kit online, swabbed their cheeks and sent their samples to the Genographic lab for processing. This unprecedented collection of samples and data is a scientific resource that the project plans to leverage moving forward.

Genographic Project Director and National Geographic Explorer-in-Residence Dr. Spencer Wells noted, "The Basque research is a wonderful example of how we are studying the extensive Genographic sample collection using the most advanced genetic methods. In some cases, the most appropriate tool may be mtDNA, while in others the Y-chromosome or autosomal markers may be more informative. Ultimately, the goal of the project is to use the latest genetic technology to understand how our ancestors populated the planet."

Ω

The Genographic Project has announced the most comprehensive analysis to date of Basque genetic patterns, showing that Basque genetic uniqueness predates the arrival of agriculture in the Iberian Peninsula some 7,000 years ago. Through detailed DNA analysis of samples from the French and Spanish Basque regions, the Genographic team found that Basques share unique genetic patterns that distinguish them from the surrounding non-Basque populations.

Published in the American Journal of Human Genetics, the study was led by Lluis Quintana-Murci, principal investigator of Genographic's Western European regional center. "Our study mirrors European history and could certainly extend to other European peoples. We found that Basques share common genetic features with other European populations, but at the same time present some autochthonous (local) lineages that make them unique," said Quintana-Murci. "This is reflected in their language, Euskara, a non-Indo-European language, which altogether contributes to the cultural richness of this European population."

The genetic finding parallels previous studies of the Basque language, which has been found to be a linguistic isolate, unrelated to any other language in the world. It is the ancestral language of the Basque people who inhabit a region spanning northeastern Spain and southwestern France and has long been thought to trace back to the languages spoken in Europe prior to the arrival of the Indo-European languages more than 4,000 years ago. (English, Spanish, French and most other European languages are Indo-European.)

Genographic Project researchers studied mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), which has been widely applied to the study of human history and is perhaps best known as the tool used to reveal 'Mitchondrial Eve,' the female common ancestor of all modern humans who lived in Africa approximately 200,000 years ago. It has also been used to study regional variation both within and outside Africa, providing detailed insights into more recent migration patterns.

The Genographic Project, launched in 2005, enters its eighth year this spring. Nearly 75,000 participants from over 1,000 indigenous populations around the world have joined the initiative, along with more than 440,000 members of the general public who have purchased a testing kit online, swabbed their cheeks and sent their samples to the Genographic lab for processing. This unprecedented collection of samples and data is a scientific resource that the project plans to leverage moving forward.

Genographic Project Director and National Geographic Explorer-in-Residence Dr. Spencer Wells noted, "The Basque research is a wonderful example of how we are studying the extensive Genographic sample collection using the most advanced genetic methods. In some cases, the most appropriate tool may be mtDNA, while in others the Y-chromosome or autosomal markers may be more informative. Ultimately, the goal of the project is to use the latest genetic technology to understand how our ancestors populated the planet."

Ω

Tuesday, March 6, 2012

Exploration of Mythical David and Goliath Battle Site

Ω

New archaeological dig in biblical city of Azekah

This summer, Tel Aviv University's Sonia and Marco Nadler Institute of Archaeology is adding another excavation to their already expansive list of seven active digs. Azekah, a city of the ancient kingdom of Judah that features prominently in the Bible — both as a main border city and the fortification which towers above the Ellah valley — is the site of the legendary battle between David and giant Goliath.

The Assyrian king Sennacherib described Azekah as "an eagle's nest ... with towers that project to the sky like swords." The Judahite stronghold bordered the land of the Philistines and was strategically positioned for military action and trade. This culturally significant city could hold the answer to historically significant riddles about the development of the Kingdom of Judah, the relationship between Judah and its neighbors, and the Judahite culture.

After years of excavation at Ramat Rahel near Jerusalem, the heart of the Kingdom of Judah, the researchers are looking to Azekah for insight into what life was like on the periphery of that ancient kingdom. "We are asking questions about the history of Judah from the westernmost border," says Prof. Lipschits, noting that the main Philistine Kingdom of Gat was located just a few kilometres to the west of Azekah. The site probably served as the setting for the tale of David and Goliath, the story of an unlikely Judahite hero who overcame the Philistine's champion warrior, because Azikah was truly "a meeting point of the two different cultures," he explains.

Beyond its cultural significance, Azekah was also a gateway to the Judahite kingdom, positioned along the main roads leading from the coastal plains to the Judean Hills at the heart of the kingdom. Although the city flourished for millennia, its natural riches and strategic position made it an inviting target for foreign powers.

The researchers hope that extraordinary findings await them beneath the destruction layers of the city, which was conquered in 701 B.C.E. by the Assyrians and in 586 B.C.E. by the Babylonians. When a site is abandoned, the people who once lived there would usually collect their gatherings and move on. But this wasn't possible in the wake of a sudden and catastrophic event, such as war, says Dr. Gadot. Under the destruction layer, cultural artefacts are well-preserved, and there could also be remnants of an invasion, like a siege ramp, like the one that was found in the Judahite city of Lachich.

Ω

New archaeological dig in biblical city of Azekah

This summer, Tel Aviv University's Sonia and Marco Nadler Institute of Archaeology is adding another excavation to their already expansive list of seven active digs. Azekah, a city of the ancient kingdom of Judah that features prominently in the Bible — both as a main border city and the fortification which towers above the Ellah valley — is the site of the legendary battle between David and giant Goliath.

The Assyrian king Sennacherib described Azekah as "an eagle's nest ... with towers that project to the sky like swords." The Judahite stronghold bordered the land of the Philistines and was strategically positioned for military action and trade. This culturally significant city could hold the answer to historically significant riddles about the development of the Kingdom of Judah, the relationship between Judah and its neighbors, and the Judahite culture.

After years of excavation at Ramat Rahel near Jerusalem, the heart of the Kingdom of Judah, the researchers are looking to Azekah for insight into what life was like on the periphery of that ancient kingdom. "We are asking questions about the history of Judah from the westernmost border," says Prof. Lipschits, noting that the main Philistine Kingdom of Gat was located just a few kilometres to the west of Azekah. The site probably served as the setting for the tale of David and Goliath, the story of an unlikely Judahite hero who overcame the Philistine's champion warrior, because Azikah was truly "a meeting point of the two different cultures," he explains.

Beyond its cultural significance, Azekah was also a gateway to the Judahite kingdom, positioned along the main roads leading from the coastal plains to the Judean Hills at the heart of the kingdom. Although the city flourished for millennia, its natural riches and strategic position made it an inviting target for foreign powers.

The researchers hope that extraordinary findings await them beneath the destruction layers of the city, which was conquered in 701 B.C.E. by the Assyrians and in 586 B.C.E. by the Babylonians. When a site is abandoned, the people who once lived there would usually collect their gatherings and move on. But this wasn't possible in the wake of a sudden and catastrophic event, such as war, says Dr. Gadot. Under the destruction layer, cultural artefacts are well-preserved, and there could also be remnants of an invasion, like a siege ramp, like the one that was found in the Judahite city of Lachich.

Ω

Ancient "Graffiti" Unlock the Life of the Common Man

Ω

An ancient Greek graffito from Beth She'arim

History is often shaped by the stories of kings and religious and military leaders, and much of what we know about the past derives from official sources like military records and governmental decrees. Now an international project is gaining invaluable insights into the history of ancient Israel through the collection and analysis of inscriptions — pieces of common writing that include anything from a single word to a love poem, epitaph, declaration, or question about faith, and everything in between that does not appear in a book or on a coin.

Such writing on the walls — or column, stone, tomb, floor, or mosaic — is essential to a scholar's toolbox, explains Prof. Jonathan Price of Tel Aviv University's Department of Classics. Along with his colleague Prof. Benjamin Isaac, Prof. Hannah Cotton of Hebrew University and Prof. Werner Eck of the University of Cologne, he is a contributing editor to a series of volumes that presents the written remains of the lives of common individuals in Israel, as well as adding important information about provincial administration and religious institutions, during the period between Alexander the Great and the rise of Islam (the fourth century B.C.E. to the seventh century C.E.).

These are the tweets of antiquity.

There has never been such a large-scale effort to recover inscriptions in a multi-lingual publication. Previous collections have been limited to the viewpoints of single cultures, topics, or languages. This innovative series seeks to uncover the whole story of a given site by incorporating inscriptions of every subject, length, and language, publishing them side by side. In antiquity, the part of the world that is now modern Israel was intensely multilingual, multicultural, and highly literate, says Prof. Price, who has presented the project at several conferences, and will present it again this fall in San Francisco and Philadelphia. When the volumes are complete, they will include an analysis of about 12,000 inscriptions in more than ten languages.

History's "scrap paper"

The project represents countless hours spent in museum storerooms, church basements, caves and archaeological sites, says Prof. Price, who notes that all the researchers involved have been dedicated to analyzing inscriptions straight from the physical objects on which they are written whenever possible, instead of drawings, photos or reproductions. The team has already discovered a great amount of material that has never been published before.

Each text is analyzed, translated, and published with commentary by top scholars. Researchers work to overcome the challenges of incomplete inscriptions, often eroded from their "canvas" with time, and sometimes poor use of grammar and spelling, which represent different levels in education and reading and writing capabilities — or simply the informal nature of the text. Scholars thousands of years in the future might face similar difficulties when trying to decipher the language of our own text messages or emails.

Most of these inscriptions, especially the thousands of epitaphs, are written by average people, their names not recorded in any other source. This makes them indispensable for social, cultural, and religious history, suggests Prof. Price. "They give us information about what people believed, the languages they spoke, relationships between families, their occupations — daily life," he says. "We don't have this from any other source."

The first volume, edited by Prof. Price, Prof. Isaac, and others and focusing on Jerusalem up to and through the first century C.E., has already been published. New volumes will be published regularly until the project comes to a close in 2017, resulting in approximately nine volumes.

"I was here"

Graffiti, which comprise a significant amount of the collected inscriptions, are a common phenomenon throughout the ancient world. Famously, the walls of the city of Pompeii were covered with graffiti, including advertisements, poetry, and lewd sketches. In ancient Israel, people also left behind small traces of their lives — although discussion of belief systems, personal appeals to God, and hopes for the future are more prevalent than the sexual innuendo that adorns the walls of Pompeii.

"These are the only remains of real people. Thousands whose voices have disappeared into the oblivion of history," notes Prof. Price. These writings are, and have always been, a way for people to perpetuate their memory and mark their existence.

Of course, our world has its graffiti too. It's not hard to find, from subway doors and bathroom stalls to protected archaeological sites. Although it may be considered bothersome and disrespectful now, "in two thousand years, it'll be interesting to scholars," Prof. Price says with a smile.

Ω

An ancient Greek graffito from Beth She'arim

History is often shaped by the stories of kings and religious and military leaders, and much of what we know about the past derives from official sources like military records and governmental decrees. Now an international project is gaining invaluable insights into the history of ancient Israel through the collection and analysis of inscriptions — pieces of common writing that include anything from a single word to a love poem, epitaph, declaration, or question about faith, and everything in between that does not appear in a book or on a coin.

Such writing on the walls — or column, stone, tomb, floor, or mosaic — is essential to a scholar's toolbox, explains Prof. Jonathan Price of Tel Aviv University's Department of Classics. Along with his colleague Prof. Benjamin Isaac, Prof. Hannah Cotton of Hebrew University and Prof. Werner Eck of the University of Cologne, he is a contributing editor to a series of volumes that presents the written remains of the lives of common individuals in Israel, as well as adding important information about provincial administration and religious institutions, during the period between Alexander the Great and the rise of Islam (the fourth century B.C.E. to the seventh century C.E.).

These are the tweets of antiquity.

There has never been such a large-scale effort to recover inscriptions in a multi-lingual publication. Previous collections have been limited to the viewpoints of single cultures, topics, or languages. This innovative series seeks to uncover the whole story of a given site by incorporating inscriptions of every subject, length, and language, publishing them side by side. In antiquity, the part of the world that is now modern Israel was intensely multilingual, multicultural, and highly literate, says Prof. Price, who has presented the project at several conferences, and will present it again this fall in San Francisco and Philadelphia. When the volumes are complete, they will include an analysis of about 12,000 inscriptions in more than ten languages.

History's "scrap paper"

The project represents countless hours spent in museum storerooms, church basements, caves and archaeological sites, says Prof. Price, who notes that all the researchers involved have been dedicated to analyzing inscriptions straight from the physical objects on which they are written whenever possible, instead of drawings, photos or reproductions. The team has already discovered a great amount of material that has never been published before.

Each text is analyzed, translated, and published with commentary by top scholars. Researchers work to overcome the challenges of incomplete inscriptions, often eroded from their "canvas" with time, and sometimes poor use of grammar and spelling, which represent different levels in education and reading and writing capabilities — or simply the informal nature of the text. Scholars thousands of years in the future might face similar difficulties when trying to decipher the language of our own text messages or emails.

Most of these inscriptions, especially the thousands of epitaphs, are written by average people, their names not recorded in any other source. This makes them indispensable for social, cultural, and religious history, suggests Prof. Price. "They give us information about what people believed, the languages they spoke, relationships between families, their occupations — daily life," he says. "We don't have this from any other source."

The first volume, edited by Prof. Price, Prof. Isaac, and others and focusing on Jerusalem up to and through the first century C.E., has already been published. New volumes will be published regularly until the project comes to a close in 2017, resulting in approximately nine volumes.

"I was here"

Graffiti, which comprise a significant amount of the collected inscriptions, are a common phenomenon throughout the ancient world. Famously, the walls of the city of Pompeii were covered with graffiti, including advertisements, poetry, and lewd sketches. In ancient Israel, people also left behind small traces of their lives — although discussion of belief systems, personal appeals to God, and hopes for the future are more prevalent than the sexual innuendo that adorns the walls of Pompeii.

"These are the only remains of real people. Thousands whose voices have disappeared into the oblivion of history," notes Prof. Price. These writings are, and have always been, a way for people to perpetuate their memory and mark their existence.

Of course, our world has its graffiti too. It's not hard to find, from subway doors and bathroom stalls to protected archaeological sites. Although it may be considered bothersome and disrespectful now, "in two thousand years, it'll be interesting to scholars," Prof. Price says with a smile.

Ω

Thursday, March 1, 2012

Research Reveals First Evidence of Hunting by Prehistoric Ohioans

Ω

Cut marks found on Ice Age bones indicate that humans in Ohio hunted or scavenged animal meat earlier than previously known. Dr. Brian Redmond, curator of archaeology at The Cleveland Museum of Natural History, was lead author on research published in the Feb. 22, 2012 online issue of the journal World Archaeology.

Redmond and researchers analyzed 10 animal bones found in 1998 in the collections of the Firelands Historical Society Museum in Norwalk, Ohio. Found by society member and co-author Matthew Burr, the bones were from a Jefferson’s Ground Sloth. This large plant-eating animal became extinct at the end of the Ice Age around 10,000 years ago.

“This research provides the first scientific evidence for hunting or scavenging of Ice Age sloth in North America,” said Redmond. “The significant age of the remains makes them the oldest evidence of prehistoric human activity in Ohio, occurring in the Late Pleistocene period.”

A series of 41 incisions appear on the animal’s left femur. Radiocarbon dating of the femur bone estimates its age to be between 13,435 to 13,738 years old. Microscopic analyses of the cut marks revealed that stone tools made the marks. The pattern and location of the distinct incisions indicate the filleting of leg muscles. No traces of the use of modern, metal cutting tools were found, so the marks are not the result of damage incurred during their unearthing. Instead, the morphology of the marks reveals that they were made by sharp-edged stone flakes or blades.

The “Firelands Ground Sloth,” as the specimen is named, is one of only three specimens of Megalonyx jeffersonii known from Ohio. Based on measurements of the femur, tibia and other bones, it is one of the largest individuals of this species on record. It had an estimated body mass of 1,295 kilograms (2,855 pounds).

Cut marks found on Ice Age bones indicate that humans in Ohio hunted or scavenged animal meat earlier than previously known. Dr. Brian Redmond, curator of archaeology at The Cleveland Museum of Natural History, was lead author on research published in the Feb. 22, 2012 online issue of the journal World Archaeology.

Redmond and researchers analyzed 10 animal bones found in 1998 in the collections of the Firelands Historical Society Museum in Norwalk, Ohio. Found by society member and co-author Matthew Burr, the bones were from a Jefferson’s Ground Sloth. This large plant-eating animal became extinct at the end of the Ice Age around 10,000 years ago.

“This research provides the first scientific evidence for hunting or scavenging of Ice Age sloth in North America,” said Redmond. “The significant age of the remains makes them the oldest evidence of prehistoric human activity in Ohio, occurring in the Late Pleistocene period.”

A series of 41 incisions appear on the animal’s left femur. Radiocarbon dating of the femur bone estimates its age to be between 13,435 to 13,738 years old. Microscopic analyses of the cut marks revealed that stone tools made the marks. The pattern and location of the distinct incisions indicate the filleting of leg muscles. No traces of the use of modern, metal cutting tools were found, so the marks are not the result of damage incurred during their unearthing. Instead, the morphology of the marks reveals that they were made by sharp-edged stone flakes or blades.

The “Firelands Ground Sloth,” as the specimen is named, is one of only three specimens of Megalonyx jeffersonii known from Ohio. Based on measurements of the femur, tibia and other bones, it is one of the largest individuals of this species on record. It had an estimated body mass of 1,295 kilograms (2,855 pounds).

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)