A Qur’an manuscript held by the University of Birmingham has been

placed among the oldest in the world thanks to modern scientific

methods.

Radiocarbon analysis has dated the parchment on which the text is written to the period between AD 568 and 645 with 95.4% accuracy. The test was carried out in a laboratory at the University of Oxford. The result places the leaves close to the time of the Prophet Muhammad, who is generally thought to have lived between AD 570 and 632.

Researchers conclude that the Qur’an manuscript is among the earliest written textual evidence of the Islamic holy book known to survive. This gives the Qur’an manuscript in Birmingham global significance to Muslim heritage and the study of Islam.

Susan Worrall, Director of Special Collections (Cadbury Research Library), at the University of Birmingham, said: ‘The radiocarbon dating has delivered an exciting result, which contributes significantly to our understanding of the earliest written copies of the Qur’an. We are thrilled that such an important historical document is here in Birmingham, the most culturally diverse city in the UK.’

The Qur’an manuscript is part of the University’s Mingana Collection of Middle Eastern manuscripts, held in the Cadbury Research Library. Funded by Quaker philanthropist Edward Cadbury, the collection was acquired to raise the status of Birmingham as an intellectual centre for religious studies and attract prominent theological scholars.

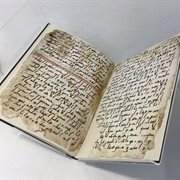

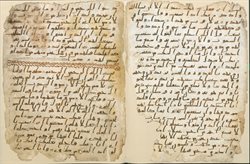

Consisting of two parchment leaves, the Qur’an manuscript contains parts of Suras (chapters) 18 to 20, written with ink in an early form of Arabic script known as Hijazi. For many years, the manuscript had been misbound with leaves of a similar Qur’an manuscript, which is datable to the late seventh century.

Susan Worrall said: ‘By separating the two leaves and analysing the parchment, we have brought to light an amazing find within the Mingana Collection.’

Dr Alba Fedeli, who studied the leaves as part of her PhD research, said: ‘The two leaves, which were radiocarbon dated to the early part of the seventh century, come from the same codex as a manuscript kept in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in Paris.’

Explaining the context and significance of the discovery, Professor David Thomas, Professor of Christianity and Islam and Nadir Dinshaw Professor of

‘According to Muslim tradition, the Prophet Muhammad received the revelations that form the Qur’an, the scripture of Islam, between the years AD 610 and 632, the year of his death. At this time, the divine message was not compiled into the book form in which it appears today. Instead, the revelations were preserved in “the memories of men”. Parts of it had also been written down on parchment, stone, palm leaves and the shoulder blades of camels. Caliph Abu Bakr, the first leader of the Muslim community after Muhammad, ordered the collection of all Qur’anic material in the form of a book. The final, authoritative written form was completed and fixed under the direction of the third leader, Caliph Uthman, in about AD 650.

‘Muslims believe that the Qur’an they read today is the same text that was standardised under Uthman and regard it as the exact record of the revelations that were delivered to Muhammad.

‘The tests carried out on the parchment of the Birmingham folios yield the strong probability that the animal from which it was taken was alive during the lifetime of the Prophet Muhammad or shortly afterwards. This means that the parts of the Qur’an that are written on this parchment can, with a degree of confidence, be dated to less than two decades after Muhammad’s death. These portions must have been in a form that is very close to the form of the Qur’an read today, supporting the view that the text has undergone little or no alteration and that it can be dated to a point very close to the time it was believed to be revealed.’

Dr Muhammad Isa Waley, Lead Curator for Persian and Turkish Manuscripts at the British Library, said: ‘This is indeed an exciting discovery. We know now that these two folios, in a beautiful and surprisingly legible Hijazi hand, almost certainly date from the time of the first three Caliphs. According to the classic accounts, it was under the third Caliph, Uthman ibn Affan, that the Qur’anic text was compiled and edited in the order of Suras familiar today, chiefly on the basis of the text as compiled by Zayd ibn Thabit under the first Caliph, Abu Bakr. Copies of the definitive edition were then distributed to the main cities under Muslim rule.

‘The Muslim community was not wealthy enough to stockpile animal skins for decades, and to produce a complete Mushaf, or copy, of the Holy Qur’an required a great many of them. The carbon dating evidence, then, indicates that Birmingham’s Cadbury Research Library is home to some precious survivors that – in view of the Suras included – would once have been at the centre of a Mushaf from that period. And it seems to leave open the possibility that the Uthmanic redaction took place earlier than had been thought – or even, conceivably, that these folios predate that process. In any case, this – along with the sheer beauty of the content and the surprisingly clear Hijazi script – is news to rejoice Muslim hearts.’

Shay Halevi

Shay Halevi.jpg)

.jpg)