Ancient genomes recovered from skeletal material found at 39 archaeological sites indicate that the Xinjiang region of China was settled by people with central and eastern Eurasian Steppe ancestry during the Bronze Age, while the region received an inflow of people with East and Central Asian ancestry during the end of the Bronze Age and the start of the Iron Age. The findings by Vikas Kumar and colleagues offer a unique window into population shifts and perhaps the spread of important metallurgical technologies and foods such as barley and wheat through this historically busy crossroads region between east and west Eurasia.

After sampling genomes from 201 individuals at the archaeological sites, Kumar et al. conclude that Xinjiang’s Bronze Age (about 5000-3000 years ago) populations were characterized by Steppe, Tarim Basin, and Central Asian ancestry until the late Bronze Age (around 3000 years ago), when populations with East and Central Asian ancestry came into the region. Xinjiang populations became genetically mixed throughout the Iron Age and into the Historical Era (from about 2000 years ago), but a core Steppe component has remained, suggesting some genetic continuity since the Iron Age. This type of continuity is surprising, the authors suggest, since it usually occurs in populations that have been much more geographically isolated than those in Xinjiang.

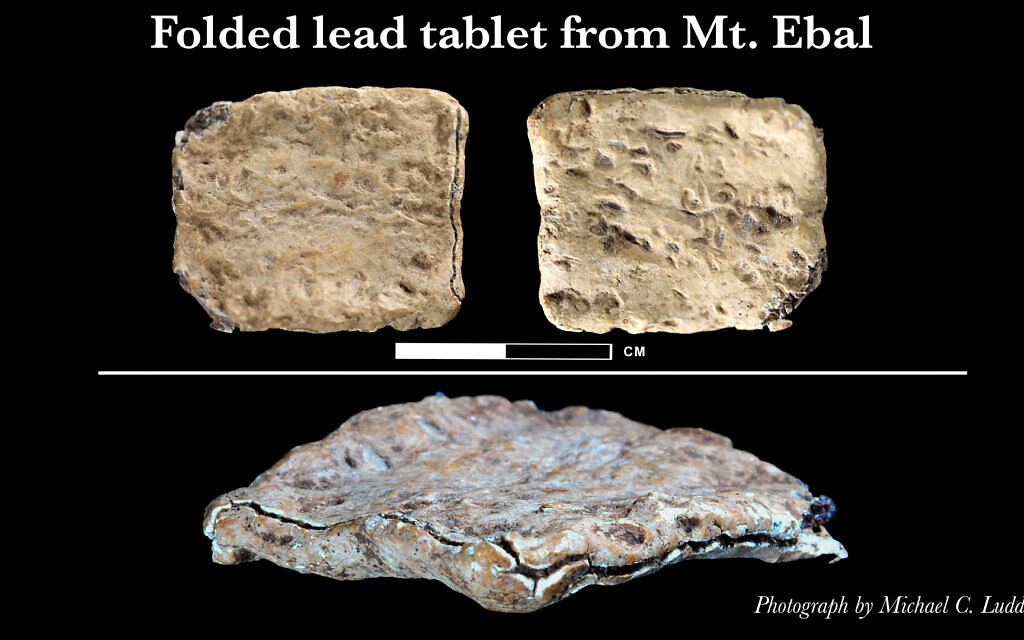

IMAGE: OVERLOOK OF TOMBS IN HIGH ALTITUDES. EXCAVATED FROM JIERZANKALE SITE IN TASHIKUERGAN, KASHI REGION view more

CREDIT: YAN XUGUANG, KASHI DAILY

Xinjiang, in northwest China, lays at an important junction between east and west Eurasia and has played a historically important role in the exchange of goods and technologies between these two regions along the Silk Road. It is a complex mix of cultures and populations.

However, the interflow and blending of these diverse populations in Xinjiang can be traced further back. Bronze Age mummies discovered in Tarim Basin were purported to have western features and textiles, and the discovery of 5th century C.E. texts of an extinct Indo-European language group, Tocharian, has spurred great interest in archeologists, linguists, and anthropologists.

Now, a research team led by Prof. FU Qiaomei from the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (IVPP) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences has unravel the past population history of Xinjiang, China, based on information from 201 ancient genomes from 39 archeological sites.

Their findings were published in Science on March 31.

A mix of local northern Asian and western Steppe ancestry in Bronze Age

The peopling of Bronze Age Xinjiang is key to understand the later population dynamics of the region. It had been proposed that the Bronze Age settling of the Tarim Basin was originally by people related to either western Steppe Cultures ("Steppe hypothesis") or Central Asian populations related to the Bactria Margiana Complex (BMAC) ("Bactrian oasis hypothesis").

FU and her team discovered the earliest inhabitants of Xinjiang showed genomic similarities with both of these groups, but broadly mixed with a unique ancestry found in the local Tarim Basin mummies, who were recently shown to be linked to a population found 25,000 years ago in southern Siberia known as the Ancient North Eurasians (ANE).

"In all, Bronze Age Xinjiang populations were found to contain ancestral components of the 'local' Tarim Basin population mixed to varying degrees with those of three groups from the surrounding regions: the Afanasievo, an Indo-European-associated Steppe culture, a group called the Chemurchek, who contained BMAC ancestry from Central Asia, and ancestry from a Northeast Asian population called the Shamanka," said Prof. FU, the last corresponding author of this paper.

The appearance of an individual with almost exclusive Northeast Asian ancestry in northern Xinjiang at this time indicated these early populations may have been already highly mobile. This evidence fits a scenario where incoming Steppe, Chemurchek and Northeast Asian populations entered the region and mixing with the existing inhabitants, who are closest to the oldest Tarim Basin mummies.

In the later part of the Bronze Age, they found the existing genomic profiles shifted to include an influx of a newer western Steppe group linked to the Steppe Middle-Late Bronze Age (MLBA) Andronovo culture, as well as an increasing influx of ancestry from East Asia found in southern Siberia. Furthermore, an expansion of ancestry related to Central Asia (BMAC) at this time indicated an increase in interactions with Central Asia across the Inner Asian Mountain Corridor.

Early entry of Indo-European speakers in Bronze Age Xinjiang

Interestingly, they also found ancestry of several Early Bronze Age individuals identified as unmixed Afanasievo ancestry. This finding corroborates an early entry of these Indo-Europeans, who may have played a role in introducing Tocharian languages to Xinjiang, the easternmost Indo-European languages recorded. This early date would make the appearance of Indo-European languages in Xinjiang roughly contemporary with their entrance into Western Europe, clarifying the origin and spread of the language family with the largest number of speakers today.

Iron Age influx of East and Central Asians established the ancestry still present today

Compared to the Bronze Age, Iron Age populations showed an increased influx of people from East and Central Asia, with the presence of the East Asian component following a West-to-East gradient of increasing East Asian ancestry. Unlike the Northeast Asian ancestry present during the Bronze Age, the East Asian ancestry entering during the Iron Age showed more diverse origins including mainland East Asia.

These Iron Age populations could be linked to populations such as the Xiongnu and Han, which coincided with a historically documented westward expansion of Xiongnu in ~2200 BP after the defeat of Yuezhi in Gansu region. Additional Iron Age movements of people from Central Asia or the Indus periphery region into Xinjiang supported early activity along routes such as the Inner Asian Mountain Corridor.

The Iron Age appearance of ancestry linked to the Sakas, a nomadic confederation derived from the Iranian peoples, helps to date the entrance of Indo-Iranian languages like Khotanese, known to be spoken by the Sakas, into Xinjiang. This Iron Age genetic profile of the region, linking Steppe, East Asian, and Central Asian people, was found to have been maintained into the Historical Era (HE). Despite the cultural shifts of the past millennia, similar ancestries to those established in the Iron Age are still observed in present day Xinjiang populations.

Phenotypic analysis of several remains, the first reported for ancient Xinjiang, gave depth to the genetic results. The majority of individuals investigated had dark brown to black hair and brown eye color throughout Bronze Age, Iron Age, and HE. Corresponded with the appearance of Andronovo Steppe ancestry, a small proportion of the Iron Age individuals are marked blond hair, blue eyes and lighter skin tone in the west and north of Xinjiang. Two Early Bronze Age Tarim Basin mummies in east Xinjiang were found likely to have had dark brown to black hair and darker skin, despite their archeologically-identified "western" features, and a more recent third mummy from the Late Bronze Age was likely to have had a more intermediate skin tone.

"With the widespread population movements documented in the study, it is intriguing to see the degree of genetic continuity that has been maintained in Xinjiang over the past 5000 years." said Associate Prof. Vikas KUMAR from IVPP, the first author of this study.

"What is striking about these results is that the demographic history of a cross-roads region as Xinjiang has been marked not by population replacements, but by the genetic incorporation of diverse incoming cultural groups into the existing population, making Xinjiang a true 'melting-pot'," said Prof. FU.

This detailed aspect had not been so clear looking only at archeological and cultural evidence. These findings suggest the importance of combining genetic and archaeological evidence to provide a more comprehensive insight into population history.

The current ancient DNA analysis highlights a holistic approach to unravelling the complex history of locations like Xinjiang, where the many interactions between different groups and cultures in the past make detailed demographic studies difficult. Future studies in this area could reveal more about the finer points of Xinjiang's history.

JOURNAL

Science