The history of the Caribbean's original islanders comes into sharper focus in a new Nature study that combines decades of archaeological work with advancements in genetic technology.

An international team led by Harvard Medical School's David Reich analyzed the genomes of 263 individuals in the largest study of ancient human DNA in the Americas to date. The genetics trace two major migratory waves in the Caribbean by two distinct groups, thousands of years apart, revealing an archipelago settled by highly mobile people, with distant relatives often living on different islands.

Reich's lab also developed a new genetic technique for estimating past population size, showing the number of people living in the Caribbean when Europeans arrived was far smaller than previously thought -- likely in the tens of thousands, rather than the million or more reported by Columbus and his successors.

For archaeologist William Keegan, whose work in the Caribbean spans more than 40 years, ancient DNA offers a powerful new tool to help resolve longstanding debates, confirm hypotheses and spotlight remaining mysteries.

This "moves our understanding of the Caribbean forward dramatically in one fell swoop," said Keegan, curator at the Florida Museum of Natural History and co-senior author of the study. "The methods David's team developed helped address questions I didn't even know we could address."

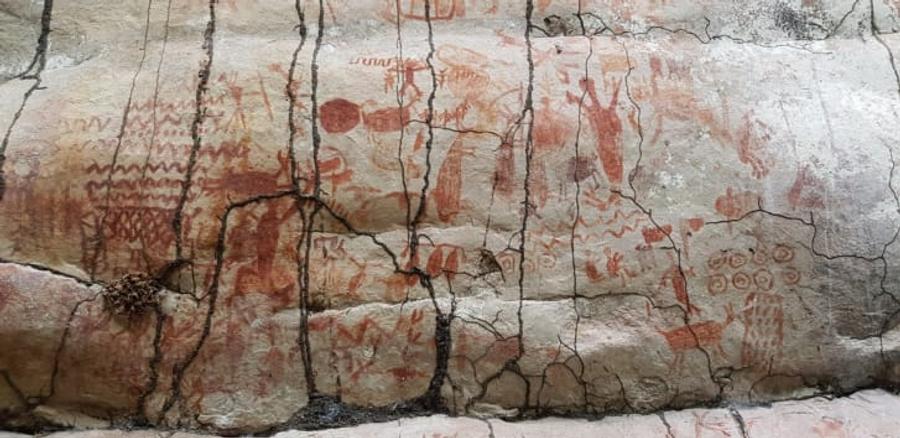

Archaeologists often rely on the remnants of domestic life -- pottery, tools, bone and shell discards -- to piece together the past. Now, technological breakthroughs in the study of ancient DNA are shedding new light on the movement of animals and humans, particularly in the Caribbean where each island can be a unique microcosm of life.

While the heat and humidity of the tropics can quickly break down organic matter, the human body contains a lockbox of genetic material: a small, unusually dense part of the bone protecting the inner ear. Primarily using this structure, researchers extracted and analyzed DNA from 174 people who lived in the Caribbean and Venezuela between 400 and 3,100 years ago, combining the data with 89 previously sequenced individuals.

The team, which includes Caribbean-based scholars, received permission to carry out the genetic analysis from local governments and cultural institutions that acted as caretakers for the human remains. The authors also engaged representatives of Caribbean Indigenous communities in a discussion of their findings.

The genetic evidence offers new insights into the peopling of the Caribbean. The islands' first inhabitants, a group of stone tool-users, boated to Cuba about 6,000 years ago, gradually expanding eastward to other islands during the region's Archaic Age. Where they came from remains unclear -- while they are more closely related to Central and South Americans than to North Americans, their genetics do not match any particular Indigenous group. However, similar artifacts found in Belize and Cuba may suggest a Central American origin, Keegan said.

About 2,500-3,000 years ago, farmers and potters related to the Arawak-speakers of northeast South America established a second pathway into the Caribbean. Using the fingers of South America's Orinoco River Basin like highways, they travelled from the interior to coastal Venezuela and pushed north into the Caribbean Sea, settling Puerto Rico and eventually moving westward. Their arrival ushered in the region's Ceramic Age, marked by agriculture and the widespread production and use of pottery.

Over time, nearly all genetic traces of Archaic Age people vanished, except for a holdout community in western Cuba that persisted as late as European arrival. Intermarriage between the two groups was rare, with only three individuals in the study showing mixed ancestry.

Many present-day Cubans, Dominicans and Puerto Ricans are the descendants of Ceramic Age people, as well as European immigrants and enslaved Africans. But researchers noted only marginal evidence of Archaic Age ancestry in modern individuals.

"That's a big mystery," Keegan said. "For Cuba, it's especially curious that we don't see more Archaic ancestry."

During the Ceramic Age, Caribbean pottery underwent at least five marked shifts in style over 2,000 years. Ornate red pottery decorated with white painted designs gave way to simple, buff-colored vessels, while other pots were punctuated with tiny dots and incisions or bore sculpted animal faces that likely doubled as handles. Some archaeologists pointed to these transitions as evidence for new migrations to the islands. But DNA tells a different story, suggesting all of the styles were developed by descendants of the people who arrived in the Caribbean 2,500-3,000 years ago, though they may have interacted with and took inspiration from outsiders.

"That was a question we might not have known to ask had we not had an archaeological expert on our team," said co-first author Kendra Sirak, a postdoctoral fellow in the Reich Lab. "We document this remarkable genetic continuity across changes in ceramic style. We talk about 'pots vs. people,' and to our knowledge, it's just pots."

Highlighting the region's interconnectivity, a study of male X chromosomes uncovered 19 pairs of "genetic cousins" living on different islands -- people who share the same amount of DNA as biological cousins but may be separated by generations. In the most striking example, one man was buried in the Bahamas while his relative was laid to rest about 600 miles away in the Dominican Republic.

"Showing relationships across different islands is really an amazing step forward," said Keegan, who added that shifting winds and currents can make passage between islands difficult. "I was really surprised to see these cousin pairings between islands."

Uncovering such a high proportion of genetic cousins in a sample of fewer than 100 men is another indicator that the region's total population size was small, said Reich, professor of genetics in the Blavatnik Institute at HMS and professor of human evolutionary biology at Harvard.

"When you sample two modern individuals, you don't often find that they're close relatives," he said. "Here, we're finding relatives all over the place."

A technique developed by study co-author Harald Ringbauer, a postdoctoral fellow in the Reich Lab, used shared segments of DNA to estimate past population size, a method that could also be applied to future studies of ancient people. Ringbauer's technique showed about 10,000 to 50,000 people were living on two of the Caribbean's largest islands, Hispaniola and Puerto Rico, shortly before European arrival. This falls far short of the million inhabitants Columbus described to his patrons, likely to impress them, Keegan said.

Later, 16th-century historian Bartolomé de las Casas claimed the region had been home to 3 million people before being decimated by European enslavement and disease. While this, too, was an exaggeration, the number of people who died as a result of colonization remains an atrocity, Reich said.

"This was a systematic program of cultural erasure. The fact that the number was not 1 million or millions of people, but rather tens of thousands, does not make that erasure any less significant," he said.

For Keegan, collaborating with geneticists gave him the ability to prove some hypotheses he had argued for years -- while upending others.

"At this point, I don't care if I'm wrong or right," he said. "It's just exciting to have a firmer basis for reevaluating how we look at the past in the Caribbean. One of the most significant outcomes of this study is that it demonstrates just how important culture is in understanding human societies. Genes may be discrete, measurable units, but the human genome is culturally created."