Article Body 2010

Known as the “cradle of Chinese

civilization,” the Yellow River was the birthplace of the prosperous

northern Chinese civilizations in early Chinese history. However, the

Yellow River is also referred to as “China’s Sorrow” because of its

frequent and devastating flooding.

Research maps and images courtesy of the Journal of Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences.

For thousands of years, Mother Nature has taken the blame for tremendous

human suffering caused by massive flooding along the Yellow River, long

known in China as the “River of Sorrow” and “Scourge of the Sons of

Han.”

Now, new research from Washington University in St. Louis links the

river’s increasingly deadly floods to a widespread pattern of

human-caused environmental degradation and related flood-mitigation

efforts that began changing the river’s natural flow nearly 3,000 years

ago.

WUSTL archaeologist T.R. Kidder excavates at Sanyangzhuang, an ancient, flood-buried community known as China’s Pompeii.

“Human intervention in the Chinese environment is relatively massive,

remarkably early and nowhere more keenly witnessed than in attempts to

harness the Yellow River,” said T.R. Kidder, PhD, lead author of the

study and an archaeologist at Washington University.

“In some ways, these findings offer a new benchmark for the beginning

of the Anthropocene, the epoch in which humans became the most dominant

global force in nature.”

Forthcoming in the Journal of Archaeological and Anthropological

Sciences, the study offers the earliest known archaeological evidence

for human construction of large-scale levees and other flood-control

systems in China.

A catastrophic flood

It also suggests that the Chinese government’s long-running efforts

to tame the Yellow River with levees, dikes and drainage ditches

actually made periodic flooding much worse, setting the stage for a

catastrophic flood circa A.D. 14-17, which likely killed millions and

triggered the collapse of the Western Han Dynasty.

“New evidence from China and elsewhere show us that past societies

changed environments far more than we’ve ever suspected,” said Kidder,

the Edward S. and Tedi Macias Professor in Arts & Sciences and chair

of anthropology at WUSTL. “By 2,000 years ago, people were controlling

the Yellow River, or at least thought they were controlling it, and

that’s the problem.”

Kidder’s research, co-authored with Liu Haiwang, senior researcher at

China’s Henan Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology,

relies on a sophisticated analysis of sedimentary soils deposited along

the Yellow River over thousands of years.

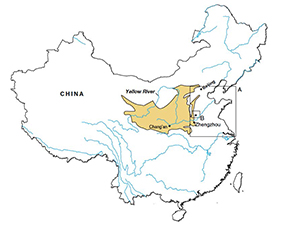

Locator Map: The Yellow River

Vallley of China, with Box A identifying the flood plain regions

researched in this study.The star in Box B is the location of the

Anshang and Sanyangzhuang sites. The approximate extent of the Loess

Plateau is indicated by shading. VIEW LARGER>

It includes data from the team’s ongoing excavations at the sites of

two ancient communities in the lower Yellow River flood plain of China’s

Henan province.

The Sanyangzhuang site, known today as “China’s Pompeii,” was slowly

buried beneath five meters of sediment during a massive flood circa A.D.

14–17, leading to exceptional preservation of its buildings, fields,

roads and wells.

The Anshang site, discovered in 2012, includes the remains of a

human-constructed levee and three irrigation/drainage ditches dating to

the Zhou Dynasty (c. 1046–256 BC).

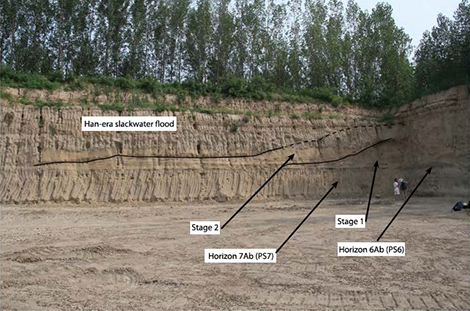

Researchers examined about 50 vertical feet of exposed

soil layers at the Anshang site, carefully cleaning sections of a quarry

wall to reveal patterns of sedimentary deposits dating back about

10,000 years. Nearly a third of this 10,000-year cross-section has been

deposited in the last 2,000 years, indicating that the rate of deposit

has steadily increased at a pace that mirrors the expansion of human

activity in the region.

The southwest corner of the brick quarry dig site at Anshang shows remnants of the bank/levee in the sedimentary record. VIEW LARGER>

While ancient levees may be difficult to spot with an untrained eye,

geoarchaeologists employ an array of precise analytic tools to confirm a

site’s sedimentary history. Soil layers are identified by coloration

and tested for physical and chemical alterations linked to human

activity. Timeframes are identified through radiocarbon dating of

freshwater snail shells and other organic soil matter.

“Thin microscopic sections of dirt samples show organization of soil

grains, revealing whether an earthen structure was human-built or laid

down as part of a natural sedimentation process,” Kidder said. “Our

analysis clearly shows that these levees are not naturally formed berms,

but are indeed artificially created through the work of humans.”

Kidder’s research suggests the Chinese began building

drainage/irrigation canals and bank/levee systems along the lower

reaches of the Yellow River about 2,900–2,700 years ago. By the

beginning of the first millennium A.D., the levee system had been

extended much farther up river, lining the banks for several hundred

miles, he estimated.

The levees were built in part because of increasing erosion upstream,

which was caused by more intensive agriculture and the expansion of the

growing Chinese civilization. The sedimentary record shows a vicious

cycle of primitive levees built larger and larger as erosion increased

and periodic floods grew more widespread and destructive.

Boxed section of Image A shows the

first stage of a bank/levee exposed in the excavation at Anshang. Image

B offers a closer view of the boxed section showing mixed and

loaded/rammed sediments near the base of the bank/levee. VIEW LARGER>

“Our evidence suggests that the first levees were built to be about

6-7 feet high, but within a decade the one at Anshang was doubled in

height and width,” Kidder said. “It’s easy to see the trap they fell

into: building levees causes sediments to accumulate in the river bed,

raising the river higher, and making it more vulnerable to flooding,

which requires you to build the levee higher, which causes the sediments

to accumulate, and the process repeats itself. The Yellow River has

been an engineered river — entirely unnatural — for quite a long time.”

Help for understanding climate change’s effects

Kidder, an authority on river basin geoarchaeology, has gathered data

from the Yellow River excavation sites over the last five summers. He

also conducts similar geoarchaeology research along the Mississippi

River at a Native American site called Poverty Point in Louisiana.

He argues that geoarchaeology — a relatively new science that

combines aspects of geology and archaeology — offers the potential to

make dramatic contributions to our understanding of how climate change

and other large-scale environmental forces are shaping human history.

While there are many theories behind the fall of the Western Han

Dynasty, Kidder’s research suggests human interaction with the

environment played a central role in its demise. In this study, he

offers a big-picture explanation for how a complex mix of

well-intentioned government policies and technological innovations

gradually led the dynasty down a disastrous path of its own making.

The Yellow River, he argues, had existed for eons as a relatively

calm and stable waterway until large numbers of Chinese farmers began

disturbing the fragile environment of the upper river’s Loess Plateau.

Built up over the ages by wind-blown sands from the nearby Gobi Desert

and Qaidam Basin, the plateau has long boasted some of the world’s most

erosion-prone soils.

As early as 700 B.C., Chinese authorities were encouraging peasant

farmers to move into remote regions of the plateau, citing the need to

feed a large and growing population while establishing a buffer of human

settlement against the threat of nomadic invaders along its northern

border. Construction of The Great Wall swelled populations still

further.

Meanwhile, new iron-making technologies vastly increased the

effectiveness of plows and other farm tools while spurring rapid

deforestation of timber used in iron refining. Widespread erosion in the

river’s upper regions caused it to carry incredibly heavy loads of

sediment downstream where deposits gradually raised the river bed above

levees and surrounding fields.

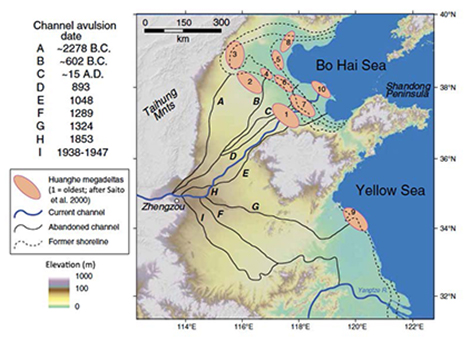

Implications for modern river management

Slowly, over thousands of years, human intervention began to have a

dramatic impact on the river’s character. Periodic breaches of the levee

system led to devastating floods, with some shifting the river’s main

channel hundreds of miles from its initial course.

Map showing historically

identified courses of the Yellow River and its historic mega-deltas. The

1938–1947 course evolved after the dykes were destroyed to

(unsuccessfully) prevent Japanese forces from advancing across the

Central Plains.

VIEW LARGER>

A census taken by China in A.D. 2 suggests the area struck by the

massive A.D. 14-17 flood was very heavily populated, with an average of

122 people per square kilometer, or approximately 9.5 million people

living directly in the flood’s path.

“The misery and suffering must have been unimaginable,” Kidder said.

Historical accounts indicate that communities hit by the flood were

soon in complete disarray, with reports of people resorting to banditry

to obtain food and stay alive. By A.D. 20-21, the flood-torn region had

become the epicenter of a popular rebellion, one that soon would spell

the end of the Western Han Dynasty’s five-century reign of power.

“The big issue here is that human beings clearly changed the

environment, and that these changes had real consequences for human

history,” Kidder said. “It happened in the past and can happen again.”

While the research offers new insight into Chinese history, it also

has interesting implications for modern river management policies around

the globe, such as those causing similar flooding problems along the

Missouri and Mississippi rivers in the United States.

“To think that we can avoid similar catastrophe today due to better

technology is a dangerous notion,” he said. “When in doubt, bet on

Mother Nature because physics will win every time.”

“Human-caused environmental change is nothing new,” Kidder said.

“We’ve been doing this for a very long time, and the magnitude of change

is increasing. Unlike ancient China, where human mistakes devastated a

single river valley, we now have the technology to make mistakes that

can cause devastation on a truly global scale.”