The fragments were being studied at UCL as part of the Arts & Humanities Research Council-funded "Projet Volterra" -- a ten year study of Roman law in its full social, legal and political context.

Corcoran and Salway found that the text belonged to the Codex Gregorianus, or Gregorian Code, a collection of laws by emperors from Hadrian (AD 117-138) to Diocletian (AD 284-305), which was published circa AD 300. Little was known about the codex's original form and there were, until now, no known copies in existence.

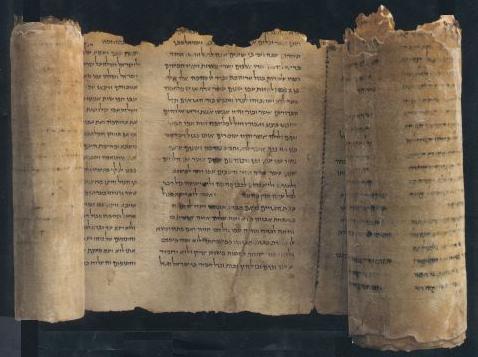

"The fragments bear the text of a Latin work in a clear calligraphic script, perhaps dating as far back as AD 400," said Dr Salway. "It uses a number of abbreviations characteristic of legal texts and the presence of writing on both sides of the fragments indicates that they belong to a page or pages from a late antique codex book -- rather than a scroll or a lawyer's loose-leaf notes.

"The fragments contain a collection of responses by a series of Roman emperors to questions on legal matters submitted by members of the public," continued Dr Salway. "The responses are arranged chronologically and grouped into thematic chapters under highlighted headings, with corrections and readers' annotations between the lines. The notes show that this particular copy received intensive use."

The surviving fragments belong to sections on appeal procedures and the statute of limitations on an as yet unidentified matter. The content is consistent with what was already known about the Gregorian Code from quotations of it in other documents, but the fragments also contain new material that has not been seen in modern times.

"These fragments are the first direct evidence of the original version of the Gregorian Code," said Dr Corcoran. "Our preliminary study confirms that it was the pioneer of a long tradition that has extended down into the modern era and it is ultimately from the title of this work, and its companion volume the Codex Hermogenianus, that we use the term 'code' in the sense of 'legal rulings'."

This particular manuscript may originate from Constantinople (modern Istanbul) and it is hoped that further work on the script and on the ancient annotations will illuminate more of its history.